Okanagan Sun: 44 years, three championships, one legacy

Story Courtesy Bowen Assman

Kelowna Capital News

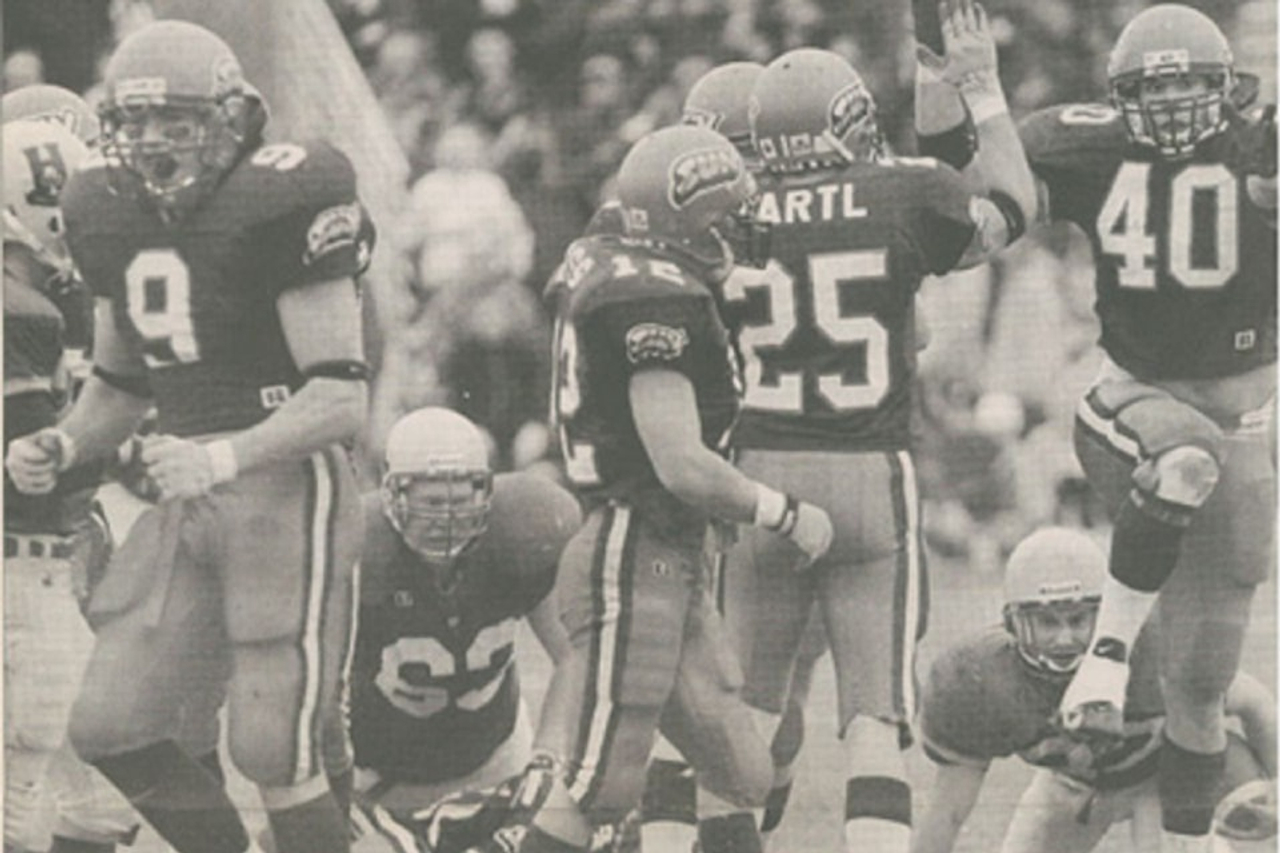

Photos Courtesy Kelowna Capital News

From their rocky start in 1981 to national glory, the Sun’s three Canadian titles tell the story of Kelowna’s football culture and community support

Kelowna's First Title (1988)

In 1981, the Okanagan Sun was born.

Co-founded by Bob Harrison and Barry Urness, the team was created out of a need for competitive junior football, for those aged 17 22 to 22, in the Okanagan Valley.

At the time, only three teams existed in the British Columbia Junior Football Association (now BCFC), under the Canadian Junior Football League (CJFL) banner.

According to Darren Prowse, a player on the inaugural team, the Sun weren’t welcomed with open arms.

“They had a hard time getting into the league, as there was a bit of Vancouver bias,” said Prowse, who was a defensive back for two seasons with the Sun. “A lot of folks thought nothing existed past Hope or Chilliwack.”

Fortunately, when the Langley Rams dropped out of the league in 1980, the Sun were able to take their spot.

That first season, it was Okanagan vs. Vancouver, as the other three league teams resided in the Lower Mainland: Renfrew Trojans (Vancouver), Richmond Raiders and Vancouver Meralomas.

In the beginning, it was a rocky start. The Sun’s first-ever game came at Empire Stadium against the Trojans, which seated more than 30,000.

“We had a lot of guys who didn’t even play football, they were just big and athletic,” said Prowse, recalling a misfit crew of loggers, labourers and bouncers. “Having their first experience in that cavernous stadium was eye-opening.”

The team’s first play from scrimmage was a handoff. It couldn’t have gone worse.

“Our offensive line was a little slow, so during the exchange, the Trojans' defensive lineman actually beat the running back to the ball, grabbed it and pranced into the endzone for a touchdown,” Prowse chuckled. “Everybody was just kind of shocked to be playing and didn't have much experience.”

The result was a 29-3 loss. However, the excitement in Kelowna for the team’s first home game was undeniable.

“Everybody in town was excited,” said Prowse. “You’d walk down the street and everybody knew you were a Sun player. We were all happy to be here.”

Prowse, a native of Red Deer, Alta., was just 17 when he suited up for the Sun. A wiry 140 pounds, he was skeptical of his abilities at first.

After playing through 1982, when the Sun finished first in the league at 7-2 before losing in the conference championship, Prowse moved into coaching.

“There was a great group of coaches with whom I worked,” said Prowse, who coached defensive backs and linebackers from 1985 to 1990.

By 1985, a new crop of rookies emerged. After third and second-place finishes in the conference, by 1988, the team was hungry, battle-tested (with 15 of those rookies from 1985 still on the roster) and dominant.

After tying Richmond in the season opener, the Sun won 11 straight, including a 50-0 blowout of the Burlington Jr. Wildcats in Ontario to win the Armadale Cup (now the Canadian Bowl).

“We had just a bunch of players who knew it was their time for a championship,” said Prowse. “And they just executed to perfection.”

Prowse later returned for another coaching stint in the late 1990s and early 2000s, lifting another title in 2000, and still lives in the Kelowna community.

He appreciated the time spent with the Sun and has seen the league grow massively from the first season.

“It was almost a beer league at the time, and now there are teams with university affiliations,” he said. “The Sun have done such a good job of offering scholarships and recruiting great people.”

Winnipeg Kid Becomes Hero (2000)

In 1998, a year out of high school and away from football, Adam Eckert and three friends loaded up a minivan in Winnipeg and drove more than 20 hours to Kelowna on a whim.

“My buddies were trying out for the Sun and told me I should come with, so I figured, why not?” Eckert said.

They arrived late at night, practiced twice the next morning, then drove back home.

“I got a phone call a few weeks later saying I made the team,” Eckert recalled. “I was shocked and wasn’t expecting it, but I had to make a decision.”

The 19-year-old, who was working at a Winnipeg grocery store at the time, still felt the football itch, so he decided to drop everything and make the trek out to the sunny Okanagan.

“It was a scary situation at the beginning," he admitted. "But I knew I wasn’t ready for college and wasn’t quite sure what I wanted to do in life. Kelowna happened to be an opportunity.”

A dual-threat in high school, Eckert played receiver for most of his three-year Sun career.

“I was only able to play offence until one crucial moment when I got the call on defence."

It was the semifinals in 2000, and the Sun hosted the Victoria Rebels. Okanagan trailed by 18 at halftime.

After storming back to force overtime, the Sun held a tedious five-point lead. With seconds left, and the Rebels marching down the field, Sun starting cornerback Andy Leeson got injured.

In stepped Eckert.

“Instead of putting in a backup corner without experience, I got the call,” he said. “I hadn’t played defence since high school, so I was pretty nervous.”

On the final play, Rebels quarterback Jon Ryan scrambled out of the pocket and locked eyes with his receiver in the end zone.

“We were playing Cover 3 defence, but I noticed Ryan’s eyes went to an unattended receiver, so I ran over there and knocked the ball over,” said Eckert.

Final score: Okanagan 43, Victoria 38.

Modest as ever, Eckert said he thought he "did all right”-- after already piling up 330 all-purpose yards on offence.

“I thought he caught it at first,” Eckert said. “We both lay on the ground and I asked him if he caught it, which he didn't. Luckily, I got just enough.”

That victory carried the Sun to the Canadian Bowl, where they beat Saskatoon 36-28. It was their first national title in 12 years, and it finally got them over the hump after three straight final losses.

“When we had our last huddle prior to the clock running out, we all looked around and had tears in our eyes,” said Eckert.

Eckert’s Sun career led to a stint in the CFL, though a finger injury limited his time.

“I cherished that moment, but I realized right away that it was a business,” he said. “People don’t see how cutthroat the pros can be with cuts, practice squads and all the prep.”

“I was up and down between starting and on the practice roster,” he said. “It wasn’t ideal, but I got to experience two Grey Cup finals. Not everyone gets the opportunity to play beyond high school and college. I truly feel like I was blessed.”

Nearly thirty years later, the memories of the Sun still spring up for Eckert, who is now a high school coach in North Dakota.

“That experience was so pure,” he said. “There was something about it as serious as we took it; there was still lots of fun to be had.”

Now, he leans on his Sun experience to teach the next generation, mainly to cherish the memories.

“In the blink of an eye, an injury can change your career, so don’t take it for granted.”

“I still talk about the city of Kelowna to this day,” he said. “I loved everything about it. They say that football is a brotherhood, and with the Okanagan Sun, it really is.”

Perfect Season Under Rookie Coach (2022)

For Travis Miller, now the Sun’s current head coach, his connection to the program began by chance.

“When I first heard about the team, I was living in Grand Prairie at the time, and we had a former player from my school, Jeff Halvorson, who played and was a big part of the Sun.”

Halverson was an all-star in 2003, rushing for 1,116 yards and 16 touchdowns. But in 2004, he collapsed while watching practice and died.

“That kind of galvanized us,” Miller said.

Miller passed up offers to play in Edmonton to follow in Halverson’s footsteps and came to Kelowna.

By his own admission, he was “a terrible player in high school.” In his first testing with the Sun, his 40-yard dash time was so slow the coaches joked it took “forever seconds.”

“But I was able to grow during my five years with the Sun,” he said. “I was a backup for two, then I started in my third before becoming a top offensive lineman and a captain.”

Miller said that he definitely “matured” and used the program the way it was meant to.

“It shaped my formative years and gave me the opportunity to get a university scholarship.”

After a U Sports career with Acadia, Miller went into coaching. In 2021, then-Sun head coach Jamie Boreham asked him to join as an assistant.

“I kind of wanted a change from the business pathway I was on, so I sold my business and came out,” said Miller. “I was the offensive coordinator and then took over as coach in 2022.”

That year, the Sun went 14-0 and edged Regina 21-19 for their third national title.

“What the team needed was somebody to help be more of a director than a dictator,” said Miller. “It was a lot of collaboration between the players and coaches. That’s how I’ve maintained my coaching: using a professional approach, establishing a leadership group and communicating with players, because that’s what this generation needs.”

The 2022 team stayed even-keeled all season.

“Everyone expected us to lose that national championship game,” Miller said. “But we didn’t let the feeling in. We put our heads down and worked from the opener to the end. It was never about one moment; we just had to perform every day.”

The following season, the Sun dropped their first game in two years, prompting a culture reset. Recruitment shifted toward team-first players rather than “me-first” athletes.

“That’s kind of why we got back to the national championship,” Miller said, referencing their 37-22 loss to St. Clair in 2023. “Getting back to that level is our direction now.”

Today, the Sun have evolved into a program built on strong support systems. Players no longer scramble for jobs or housing on their own; structures are in place to help them succeed.

“Now with recruiting, you’re selling the city, program and support,” said Miller. “Because of that, you can bring in a higher level of talent. It’s shifted from ‘you’re lucky to be here’ to ‘we want you here.’”

The Sun have sent 44 players to U Sports in the past three seasons. Miller credits the Sun’s culture and community for giving athletes opportunities on and off the field.

“Our fans are the best in Canada, the Okanagan Valley is so supportive with jobs and housing,” Miller said. “The community is phenomenal, and we are so lucky.”

Prowse agreed.

“Winning helps,” he said. “But it’s the community support that drives the success of the Sun.”

BCFC

BCFC